A procedure discussed in the Supreme Court, before judges Noam Solberg, David Mintz and Alex Stein. On 11.12.22 the verdict was given.

A procedure discussed in the Supreme Court, before judges Noam Solberg, David Mintz and Alex Stein. On 11.12.22 the verdict was given.

The procedure is a request for permission to appeal the judgment of the District Court in Tel Aviv, dated November 16, 2021 in ISA 10708-03-21, given by the Honorable Judge Jordana Sarousi. A judgment that rejected the applicant’s appeal against the decision of the Registrar of Patents, in the request for an order Extension to patent No. 148756 based on the registration of two medical preparations.

Parties: Applicant: BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM PHARMA GMBH & CO.KG; The respondent: the registrar of patents, designs and trade marks.

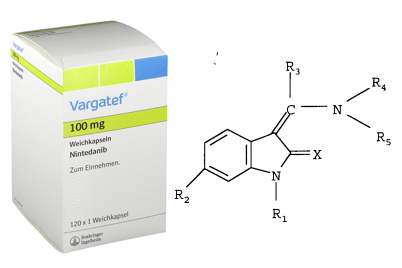

The facts: The applicant is a German pharmaceutical company, which developed the active substance Nintedanib. The active substance was registered as a European patent No. EP 1224170. At the same time, an American patent No. US 6762180 was also registered. Later, the active substance was registered as an Israeli patent No. 148756. In accordance with the patent law, the Israeli patent is valid until 12.8.21.

On November 21, 2014, approximately 15 years after the date of filing the patent, the applicant received a European marketing permit for the medicinal product named “Vagratef”, which contains the active ingredient. On January 15, 2015, the applicant received an additional European marketing permit for a medical preparation called “Ofev”, which also contains the active ingredient, but for a different medical purpose (label). For this invention, another European patent was registered in 2005 (EP 1830843 – “the additional patent”).

In the United States, a marketing permit was granted for the medicinal product Ofev on October 15, 2014. In Israel, a marketing permit was granted for both preparations on 11.12.15.

Regarding the first European patent, the applicant was granted a European SPC type extension order, which extended the validity of the reference patent by approximately five years (1,826 days), until 8/9/10/25. The American patent was granted an extension, type PTE, for an almost identical period of time (until October 1, 2025). Some time after these orders were issued, the applicant was given another European extension order, type SPC, which extends the validity of the additional patent by approximately four years (1,490 days), until 18/19.1.30. This unusual reality, in which two different SPC type extension orders were granted in Europe, for different patents referring to the same active substance, was made possible by a ‘loophole’ in European law, created by the decision of the Supreme Court of Europe (CJEU), in the case C-130/11 Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) (19.7.2012)) (“Neurim matter”). This decision created uncertainty regarding extension orders until canceled by the CJEU in its decision of 9.7.20 in case C-673/18 Santen SAS (“Santen case”).

In February 2016, the applicant submitted to the Israeli patent registrar, a request for an extension order for the Israeli patent, based on the registration of the two medical preparations. In June 2016, the Patent Authority informed the applicant that it intends to issue an extension order, in accordance with Section 64e(e)(1) of the Patent Law, for a period of 1,826 days, based on the only extension order issued at that stage in Europe (the first order). Later, as required by law, the applicant reported to the registrar about the additional extension orders issued in Europe and the United States. In November 2020, the Deputy Commissioner of Examiners at the Patent Authority informed the applicant that the Registrar intends to issue a supplementary notice of intent to issue an extension order, in accordance with Section 64e(e)(3) of the Patent Law, for a period of 1,490 days, as the length of the additional European order, until 7.11.24. This determination was based on the provision of section 64(a) of the law, which states that the protection period will be granted for a period equal to the shorter extension period among the extension periods granted to a reference patent by virtue of an order to extend a reference patent.

The applicant submitted a request for this determination to the registrar. She claimed that the deputy commissioner should have ignored the additional European order when examining the request for the extension order, because it does not meet the definition of “order to extend a reference patent” in section 64a of the law. She claimed that the legislator determined that only an extension order referring to the first marketing permit of the active substance would be taken into account. According to the applicant, the additional European order was issued based on a marketing permit that is chronologically later than the first marketing permit – that is, it is a second marketing permit for the active ingredient. The applicant referred to other sections as well, found in the B1 mark of the law, from which it appears, according to her, that the first marketing permit means the marketing permit that was given first chronologically in relation to that active substance. Also, she claimed that taking into account an extension order that can be contrary to the arrangement established by the law, means an “automatic” import of the European law that allows the granting of a double extension order, while this is contrary to the Israeli interpretation and the intention of the legislator.

Decision of the Registrar of Patents: In January 2021, the Registrar rejected the applicant’s request. The Registrar stated that the purpose of the definition listed in section 64a is to establish that only American SPC orders and PTE orders will be recognized in Israel, as opposed to other types of orders. The registrar stated that the definition detailed in the section is nothing more than a translation of the definitions anchored in European law and American law.

The applicant filed an appeal against the registrar’s decision to the district court. Meanwhile, on May 12, 2021, an extension order was issued for the basic patent, until November 7, 2024.

The District Court’s decision: The District Court rejected the applicant’s appeal.

The appellant filed a request for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court discussed the request for permission to appeal as if permission had been granted, and an appeal was filed based on the permission granted.

The results of the procedure: the appeal was accepted. It was determined that the patent registrar will update the extension order given, so that the extension period will be 1,826 days. It was also determined that the patent registrar will bear the applicant’s expenses in all courts, in the amount of NIS 25,000.

Key points discussed in the procedure:

Extension orders in the field of pharmaceuticals

The lifetime of an ordinary patent, in the countries of the world and in Israel, is 20 years from the date of submission of the application for registration of the patent. During this period, the patent grants its owner exclusive rights to exploit his invention.

In the field of pharmaceuticals, it is accepted worldwide to allow the patent holder to request its extension for an additional period, by issuing extension orders. Extending the validity of the patent is intended to compensate the patent owner for the period of time “wasted” from the date of filing the patent, until the date of receiving the marketing permit. This is because only from this date can the medical product be marketed commercially, and enjoy the rights granted by the patent. The mechanism of the extension orders is specifically required in the field of pharmaceuticals, due to the lengthening of the licensing procedures in this field, which may last several years. This figure, combined with the patent owner’s understandable incentive to submit his application for patent registration as soon as possible, so that he will not be overtaken in patent registration, thus losing the “innovation” element, results in a shortening of the effective protection period granted to the patent owner. To deal with this reality, countries in the world, including Israel, have regulated the possibility of requesting an extension of the validity of patents protecting medical products.

According to the legal arrangement established in Israel, when the conditions listed in Sections 64b and 64d of the Patent Law are met, the Registrar must extend the validity of the basic patent granted in Israel. Alongside this, with reference to the duration of the extension period, the legislator established a unique arrangement for Israel, according to which, as a general rule, the calculation of the extension period will be based on the shortest extension order given in certain countries in the world, and not in accordance with an independent calculation mechanism “Israel’s model”. That is, the registrar must extend the validity of the basic patent, for a period of time identical to the shortest period of the extension orders granted to a reference patent in a “recognized country” (USA, Italy, Great Britain, Germany, Spain and France), and subject to time “ceilings” established by law .

There are a number of extension orders abroad that are not intended to compensate for the duration of the licensing procedure, but for other purposes, and therefore are not taken into account when calculating the extension period in Israel. The definition of “attribution patent extension order” includes only two types of orders: in Europe, this is the order known as SPC; and in the United States, it is an order known as PTE.

The court explained that the settlement of the extension orders is essential, because in its absence, the company may be left without essential life-saving medical developments. However, even determining the mechanism of the extension orders does not provide a complete solution to the problem detailed above, and it can be said that, as a general rule, drug inventors receive patent protection for a much shorter period than that granted to other inventors. A comprehensive study conducted shows that the average length of time that the patents in the pharmaceutical field for effective protection are awarded is about 10. years only. About half of the effective protection period enjoyed by other patents (Ofer Tor-Sini “Extension Orders for Patents in the Pharmaceutical Field: Twenty Years to Amendment No. 3 to the Patent Law – Trends and Evaluation” Regulatory Studies D 429, 447 (2021)).

The court explained that the aspiration to protect the interest of drug inventors is the smallest element of the overall map of interests. The Israeli legislator tends to prefer the generic industry, which focuses on the “copying” of drugs, over the pharmaceutical industry, which deals with inventing drugs. There are several reasons for this. First, the public interest is to shorten the protection period, because mass, generic production often leads to a decrease of tens of percent in the price of the drug. Alongside the public good, there is another consideration that tilts the scale in favor of generic production: the generic industry in Israel is flourishing, while the pharmaceutical industry is limited in scope. Therefore, the Israeli “local” interest is to protect the generic industry. The adoption of the settlement of extension orders in Israeli law was mainly due to international pressure, which required the Israeli legislator to “align” with the accepted standards in the rest of the world, so as not to harm global trade, and to protect the international pharmaceutical companies.

The unique map of interests in Israel resulted in the creation of an arrangement, which does not independently examine the appropriate length of time for extending the patent period, in order to protect the interest of the patent holder. The main attention of the Israeli legislator is directed to what is happening abroad.

According to the law, the minimum protection period granted in another recognized country is used to determine the maximum extension period that can be granted in Israel. This, in addition to additional limitations, including maximum “ceilings” established by law. As a result, many times a shorter protection period will be granted in Israel than that granted in other countries.

Despite this, the court explained that this does not mean that in any interpretive question that arises in relation to the provisions of the law, the patent owner’s hand will be lower. The legislator recognized the need to enact a settlement of extension orders. Even if it was “forced” to do so, the State of Israel undertook, within the framework of international agreements, to maintain a certain level of protection for pharmaceutical companies, and even benefited from this: thanks to the enactment of Amendment No. 11, Israel’s path to joining the OECD was paved. Considerable weight should also be given to this figure when interpreting the provisions of the settlement. This is a particularly sensitive arrangement, which seeks to draw a delicate balance between the interest of the local generic industry of the general public, and the international interest of the pharmaceutical industry, which indirectly affects the local public interest. The court explained that in this situation, the conflicting purposes of the settlement of the extension orders, do not point to a clear and unequivocal interpretative trend, regarding the question of the length of the extension period to be granted. The purpose of the arrangement is to maintain the delicate mechanism that was put into the provisions of the law. That is, when interpreting the instructions of point B1 of the law, the interpreting judge is required to take a precise interpretation of his instructions, even when the resulting result may seem unjust. A claim of violation of the sense of justice, in itself, does not justify a deviation from the language of the law, its provisions and the delicate and intelligent balance established therein. A review of the ruling shows that this is indeed the trend that has taken root.

Interpretation of the provisions of the law

Section 64a of the law is the definitions section. Section 64d of the law lists the eligibility conditions that must be met in order to receive an extension order. Sections 64i and 64i determine the formula for calculating the validity of the extension period.

When a request for an extension order to a “basic patent” protecting an active substance, which is also protected in other countries through a “reference patent” is being considered, the registrar must extend the validity of the basic patent for a period not exceeding 5 years, which will be determined according to the duration of the shortest period, among All the extension periods stipulated in the “order to extend a reference patent”. For the purpose of calculating the extension period, the registrar is not allowed to take into account notice orders that do not meet the definition of “reference patent extension order” (SPC order in Europe and PTE order in the United States).

The court noted that in the case where a license was requested for the medicinal product that is the subject of the patent in Israel only, the law states that “the extension order shall remain in effect for a period equal to the period from the date of submission of the application for licensing to the licensing board” (Section 64T(b) of the Law). However, these cases are few. Most of the cases, as well as the case in this matter, are included in the first group of cases, which deals with cases where clearance permits were granted for the medical product in additional countries as well (Article 64T(a)). In this situation, where marketing permits were granted abroad, the licensing procedure in Israel is mainly based on the licensing procedures carried out by the foreign regulatory authorities, which leads to its shortening, to the extent that the average duration does not exceed one year. In these situations, if the legislator had determined the duration of an order The extension, based on the licensing procedures carried out in Israel, would have resulted in a significant shortening of the extension period, and a short protection would have been given to the patent owner. Therefore, in order not to overly disadvantage the pharmaceutical companies, the legislator created the unique arrangement described above.

There is no dispute that the first European patent, the American patent and the additional European patent are covered under the definition of “reference patent”, because they protect the active substance Nintedanib, which is the substance also protected by the basic patent in Israel. Also, there is no dispute that the extension orders issued in relation to the first European patent and in relation to the American patent are considered “reference patent extension orders”. The question is whether the additional European order is also considered an “order to extend a reference patent”.

There are several types of extension orders in the world. The Israeli legislator consciously chose only extension orders of a certain type – orders intended to compensate the inventor for the period of time that passed from the registration of the patent to the granting of the first marketing permit. The purpose behind the “first registration” requirement is to reduce the cases in which an extension will be granted, only to those cases where it can be assumed that the development and licensing process lasted a long time and resulted in a shortening of the effective protection period of the patent. This assumption does not hold when another medical preparation, based on the same active ingredient, was previously registered, because then there is a reasonable basis to assume that the regulatory authorities have eased the licensing requirements for the new preparation.

The two orders recognized in section 64a of the law as the “extension order for reference patent” (PTE and SPC) were intended to compensate the inventor for the time that passed from the registration of the patent to the receipt of the first marketing permit. The boxes “the first marketing permit” are found in the definition of “order to extend a reference patent”, with a deliberate intention, and they are intended to clarify that the relevant orders for the registrar’s examination are only extension orders for reference patents, which protect a medicinal product granted with regard to a first marketing permit.

The court asked the following question: What will be the law, if the foreign, American or European law changes, so that the definition of the “first marketing permit” is expanded, and will also include additional cases, which, after the enactment of Amendment No. 11, would not allow the issuance of an SPC order? In order to deal with this question, the court referred to the discussion that took place in the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee of the Knesset, regarding the relevant sections.

Automatic absorption of the foreign law

The registrar claimed that the definition in section 64a of the law is only a descriptive and technical definition, which is only intended to identify whether it is a secret order that must be taken into account. The registrar claimed that this definition was not intended to add a positive requirement that obliges him to check whether the order was issued according to the formula written in the section. This is because the positive tests he must perform – examination of the eligibility conditions for issuing a warrant – are anchored in sections 64b and 64d of the law. The court ruled that the registrar was right. In the discussion that took place in the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee of the Knesset, regarding the relevant sections, it was clarified that the patent registrar is not supposed to examine the existence of the conditions, but he accepts the order as it is. It was also clarified that this is a definition and not a positive instruction. There is no requirement or obligation for the registrar to check the said definition. However, later in the discussion, after these clarifications were given, it became clear that the wording of the definition of “order to extend a reference patent”, as brought before the committee, may raise complex questions in the future.

The method chosen by the legislator, apart from being slightly more tolerable, created an opening for a future difficulty: what will be the law, if the foreign, American or European law changes, so that the definition of the “first marketing permit” will be expanded, and will also include additional cases, seven amendment legislation No. 11 , would not allow the issuance of an SPC order?

This concern was raised by the representative of the pharmaceutical industry in the hearings of the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee (who is also the applicant’s attorney). In response to this concern, the representatives of the generic industry clarified, with the agreement of the representatives of the Ministry of Justice, that indeed, as the foreign law changes, in such a way that it will lead to the issuance of orders that are not Corresponding to the definition detailed in the law, by the recognized countries, it will not be possible to recognize these orders, for the purpose of calculating the extension period of the basic patent in Israel.

That is, already during the deliberations in the committee, the requesting attorney expressed the fear that the descriptive definition in section 64a will become a filter criterion, in the event that the foreign law changes in the future, and will no longer correspond to the definition that was “absorbed” into the Israeli law, as part of amendment number 11. The example given for this During the discussion it is: If a PTE order is defined in section 64a of the law, as one that grants a 5-year extension, and as the American law changes in the future, so that a PTE order grants a 6-year extension, this means that PTE orders issued in the US will not be recognized for the purpose of calculating the extension order For the basic patent. The solution issued in response to this is that the time limits established in foreign law, regarding the period of PTE orders, will not appear in the definition of “order to extend a reference patent”, which clarifies what a recognized PTE is, but in section 64j of the law, which deals with the Israeli limitations on the length of the order. Thus, even if the American law changes in the future, in such a way that the period of PTE orders will be extended to 6 years, there will still be recognition of orders of this type, but only up to the established “local” ceiling, i.e. 5 years. The generic industry strongly opposed this proposal.

During the committee discussion, the participants agreed that indeed, the inclusion of a detailed definition that describes the content of PTE and SPC orders, within the definition of “order to extend a reference patent”, was intended only for the purpose of defining the type of order. Also, it was clear to everyone that its role is also to prevent the automatic reception of orders that the foreign law allows, or will allow in the future, which correspond to the aforementioned definition. The participants also understood that the inclusion of the detailed definition may also have disadvantages – in the event that an order of the same type is issued, according to a different formula than the one registered in the law, or there is a change in foreign law, and PTE and SPC orders are issued that do not precisely meet the said definition, the name will have to be used as “keeper” of the threshold of the Israeli law. That is, the registrar will be required to exercise discretion, and grant an extension only to the “correct” type of orders – those issued in the course adopted by the legislator.

Following the committee’s discussion, and in order to reduce the obstacle, part of the definition appearing in the foreign law, concerning the length of the period of the issued orders, was finally omitted. SPC and PTE orders that correspond to the definition detailed as language – will come in public; Others – no. The function of the existing definition is to prevent the automatic acceptance of orders that will be recognized in the future, in the legal systems of the recognized countries.

The court clarified that contrary to the concern raised by the district court, this does not mean that the registrar has an active duty to examine whether each order was issued properly. It is not the duty of the registrar to examine whether his counterparts in other countries have neglected their duty and issued warrants contrary to the provisions of the law in their country. The registrar is required to examine whether the extension order issued in a recognized country complies with the detailed definition of “order to extend a reference patent” in Israeli law. In the event that the foreign law recognizes types of orders that do not correspond to the definition in Israeli law – the registrar has the duty not to take them into account, when determining the duration of the extension order for the basic patent. When the foreign law provides a mixture of different orders, some of which meet the definition of the law and some of which do not, the registrar has an obligation to eliminate what is not desirable. But this is a relatively simple and technical tool, according to a defined and uniform filter criterion.

The court referred to the decision in the Neurim case, which created the complication in this matter. The decision was made in 2012, more than a year before the committee hearing. At the time Amendment No. 11 was enacted, European law already allowed the issuance of SPC orders calculated in a way that does not correspond to the detailed definition that was “imported” into Israeli law. That is, at the time of Amendment No. 11, extension orders for attribution patents were already recognized in Europe, granted on the basis of marketing, which is not the “first marketing permit” of the active substance, chronologically speaking. Under these circumstances, if the legislator wanted to include such orders as part of the definition in the law, he would have to “correct” the definition in such a way that it would also refer to the additional type of orders. In order to include an SPC type order issued on the basis of a marketing permit other than the “first marketing permit”, all the legislator had to do was to omit the word “first” from the definition. Since he did not do so, it can be assumed that he requested that orders of this type not be included in the definition of “order to extend a reference patent”.

Therefore, the court explained that the legislator did not intend to automatically include SPC (or PTE) orders that will be recognized in the future under foreign law, unless they are consistent with the definition detailed in Israeli law.

Is the additional European order an SPC order that corresponds to the detailed definition established in section 64a of the law?

As mentioned, the Israeli arrangement regarding the extension of exclusivity orders is an outgrowth of international agreements, within the scope of which Israel undertook to “align the line” regarding the scope of protection to be given to medical patents, with that given in Europe and the United States. Accordingly, the Israeli arrangement, for the most part, was drafted as an almost direct translation of the relevant arrangements in the United States and the European regulation.

In the European regulation and the Israeli law, the “first registration requirement” is explicitly anchored, according to which the registration of the medical product for which the patent extension is requested, will be the first registration of the medical product that allows the use of the active ingredient in Israel. Also, the patent extension period is determined according to the time that has passed, from the date of patent registration to the receipt of the first marketing permit.

The court referred to the facts underlying the Neurim case. In 2012, the Neurim company sought to extend the validity of a patent on a drug called Circadin, based on the active substance melatonin. It soon became clear that about 17 years earlier, a previous medicine for veterinary use, based on the same active ingredient, had been registered. The question that arose in that matter was, if an extension order can be obtained, when the medical preparation that was registered early in time, was for veterinary use, while the medical preparation that is the subject of the extension order, containing the same active ingredient, was intended for human use. That is, in such a situation, is the “first registration for medical purposes” requirement actually met? In Israel, the foundations were laid to answer this question several years earlier, in a request to extend the validity of patent number 90465 Unipharma Ltd. v. H. Lundbeck A/S (published in Nebo, February 3, 2009). In the Lundbeck matter, it was determined that two different marketing permits cannot be defined, for medical preparations containing the same active ingredient, as “first to their name”. This, even when the configuration or compound in which the active ingredient appears, is not the same between the two preparations. Also in Neurim’s case, the registrar rejected the extension request ((Request for an order to extend the validity period of a patent Number 103411, which was submitted by Neurim Pharmaceutics (1991) Ltd. (published in Nebo, May 9, 2012)).

The European Court of Justice (CJEU) thought otherwise, and accepted Neurim’s request. It was determined that the definition “the first authorization to place the product on the market as a medicinal product” does not prevent the granting of an extension order for additional labeling of the same active substance, because the authorization for the new labeling can be seen as if it were an additional “first” marketing. .

Also, the CJEU ruled that as a result of this decision, for the sake of uniformity, Article 13(1) of the European Regulation, which determines how the length of SPC orders is calculated, must be interpreted in accordance with the date of receipt of the first marketing permit. It was determined that the section should be interpreted as dealing with the first marketing authorization in relation to the medicinal product for which the patent extension is requested, and not in relation to the active ingredient.

Although the decision was given in a specific context – a medicinal product for humane use, the registration of which was done after the registration of a medicinal product for veterinary use – the patent offices throughout Europe chose to interpret it in an expansive manner, and some of them even began to grant extension orders for a second indication, even when both indications were for humanitarian purposes (as in this case) . A gap has arisen between the law in Israel and the law in Europe. In Europe, a provision was accepted (as of that time) according to which two marketing permits for medical preparations for different humanitarian purposes, based on the same active substance, can be defined as “first marketing permit”. In Israel, on the other hand – no.

In this regard, the registrar determined that extension orders issued in Europe, based on the Neurim rule, fall within the scope of “an order to extend a reference patent”. This is also what the district court ruled. The Supreme Court disagreed with this position. The Supreme Court explained that judicial legislation, similar to legislative amendments made by the legislative authority, may result in a change of law. In the European regulation, there is Article 13(3), which extends the period of the SPC orders by six months, due to the lengthening of the licensing procedures regarding medical preparations that include clinical trials on children. This order is not recognized as an “order to extend a reference patent”. Automatic consideration of such an SPC order means an “automatic” importation of a foreign law provision, contrary to the intention of the legislator, unlike the detailed definition in Section 64A of the Law, and also contrary to Section 64T Sifa of the Law.

The court explained that the precise definition of the phrase “order to extend a reference patent” leaves out of bounds any type of order issued in a recognized country, which is not consistent with the detailed definition that was “absorbed” into Israeli law during the enactment of Amendment No. 11. Section 64a of the law is Although it is a literal translation of Article 13(1) of the European Regulation, from the moment the law enters the Israeli statute book, its provisions must be interpreted in accordance with the interpretation established for them in Israel.

The court explained that the CJEU’s decision in the Neurim case is based on a certain interpretation of the words “the first authorization to place the product on the market as a medicinal product”, in Article 3(d) of the European Regulation, and on the determination that there is no justification to give a different interpretation to the identical expression that appears in section 13(1). In Israel, on the other hand, the same interpretation of the “first registration requirement”, in section 64d(3) of the law (corresponding to section 3(d) of the European regulation), was rejected in the Lundbeck matter. Therefore, there is no justification to interpret section 64a of the law in a different way. In the definition of the law, the words “the first marketing permit” are used, and the registrar himself admitted that “the Israeli interpretation of the term “the first marketing permit” is different from the European interpretation.” Also, the decision regarding Neurim preceded Amendment No. 11, and the discussions that took place in the committee regarding this amendment, in which the definition “order to extend a reference patent in section 64a of the law was formulated. If the legislator was interested in having orders issued in accordance with European rulings also taken into account, he should have omitted the box” The first marketing permit,” just as Fish omitted other parts of the definition.

Also, recently the European law also changed its face, so that the secret orders that were received in Europe following the application in the Neurim case, can no longer be issued.

The court clarified that there is no determination in its decision that the registrar is required to trace the work of patent registrars abroad. The registrar is not required to examine whether the order was issued according to the formula that appears in the law. However, when the foreign law allows granting an extension order to the patent while calculating a second marketing permit , not as a mistake, but as a proactive and conscious decision, the registrar will not be able to shirk his duty to “distinguish between the impure and the pure”.