Analysis of patent infringement cases shows that most of them are based on the finding that there is no overlap between the independent claim (heart of the patent) and the accused product.

In this article, we will discuss the basic principle of drafting an independent claim in a patent that will lead to effective protection of the patent and prevent “circumvention” of the patent by competitors.

This article will not discuss the structure of patents and their components. The starting point for the reader of this article is an understanding of patent structure. For more information on this topic, please see the following article.

The Problem: Drafting an Independent Claim with multiple Unnecessary Conditions

We often examine the question of whether a product infringes a patent and find that the patent is drafted so narrowly that any change in a competing product is a substantial change that falls outside the scope of the patent monopoly.

This problem of patent inapplicability is typically due to the drafting of patents that include an independent claim with multiple conditions, which does not allow for any effective protection of the patent at the stage of filing an infringement suit, due to the multiple conditions typically included in Claim 1 of the patent – the independent claim of the patent (heart of the patent).

This problem is common in many patents because it allows the patent attorney to relatively easily pass the examination process before the patent office and the prior publication and inventive step barrier in the patent examination process. That is, by adding many unnecessary conditions, the examiner does not find a prior publication that meets all of these conditions and therefore the patent is approved for registration.

However, adding unnecessary and multiple conditions to Claim 1 makes it difficult later, in court, to argue that a particular product infringes the patent.

“Easy at the Patent Office, Difficult in Court”

A good indication of an unnecessary multi-condition claim is the number of lines in which the independent claim is written. When we see dozens of lines and dozens of conditions in the drafting of the independent claim, it is likely that the drafting will be very difficult to defend in court and it is doubtful whether a competing product will be considered infringing.

An independent claim with multiple conditions allows the infringer to easily circumvent the patent by changing and/or removing components in his product that will allow the infringer to escape the wording of the independent claim.

Case Study: Example of a Legal Case Highlighting the Issue

In the case of David Bachar v. Hamivreshet Ruhama (a patent infringement lawsuit – Civil case (Central District Court in Israel) 8706-11-12 David Bachar v. Hamivrershet Ruhama Agricultural Cooperative Society Ltd. (8.8.2013)), the court ruled that the patent’s monopoly was narrow and did not encompass the infringing product.

The relevant patent claim (Claim 1) included four key elements:

The relevant patent claim (Claim 1) included four key elements:

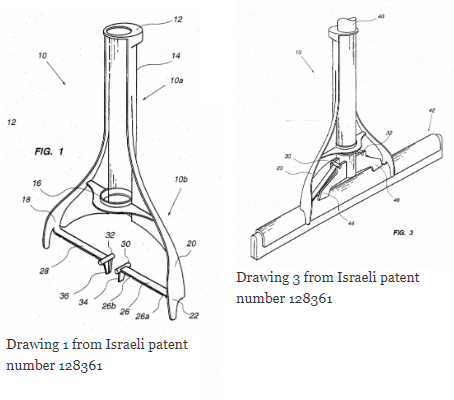

a. A pair of arms pivotally connected to the mop head (labeled 20, 18 in Figure 1).

b. The connection to the mop head is made by the inner free ends of the pair of arms (labeled 28, 26 in Figure 1).

c. The clamp carrier can be slid along the mop handle (labeled 10).

d. The device is characterized in that the pivot joint includes a stopping means to prevent unintentional detachment of the arms from the mop head (labeled 32, 30 in Figure 3).

As we can see, this is a very specific formulation for a particular product configuration, rather than a general idea.

Indeed, due to the great detail in Claim 1, the court held that the essence of the invention in the patent was an improvement relating to the problem of “unintentional release of the arms, relating to the anchoring of the arms to the mop head by means of stop teeth within housings.”

Therefore, it was ruled that the allegedly infringing product (“Magic Mop” – pictured left) is constructed, unlike the essence of the invention in the patent, of a carrier and arms cast in one piece, where the arms and the ring also form part of it. The arms of the “Magic Mop” and the ring are not connected to the mop head, and therefore this product does not infringe the patent.

This example illustrates the problem of drafting a product claim as opposed to an idea – a concept that creates an effective monopoly. A patent that ultimately does not “deliver the goods” and does not create an effective monopoly that can be defended in court.

How the Patent Should Have Been Written (Hindsight):

The patentable idea was:

A device for locking a mop head for washing floors; comprising the following components:

(1) A sleeve with at least two horizontal arms;

(2) which is slid onto the mop handle and clamps the arms to the mop;

(3) attaching the arms to the mop causes the mop head to lock onto the mop.

Solution: Broadest Possible Invention Protection – Narrow Drafting of the Independent Claim

The invention is almost always broader than the inventor thinks it is.

A good patent protects the invention as broadly as possible. Therefore, to draft a good patent, it is necessary to:

(1) Understand from the client what the heart of their invention is – what the basis of the invention is. A well-written patent claim should also take into account the inventor’s needs vis-à-vis the market – in order to prevent the market from “circumventing the patent”.

(2) Describe the “invention” in the independent claim in the narrowest way that serves the client’s purposes and the requirements of the examination process. It is advisable to draft the patent as lean as possible and at the examination stage to add elements from the dependent claims to deal with prior publications discovered at the examination stage.

(3) Distinguish the “invention” from the prior art in the field by adding essential elements.

The rule of thumb for distinguishing between good and bad patents is to focus on the length of the independent claims and the number of dependent claims. Well-drafted patents typically include a short and clear independent claim, in this way the patent is drafted broadly in a way that protects the idea rather than the specific product. The specific product is usually just a specific configuration of the idea.

Supporting Principle: Protecting an Idea, Not a Specific Product

A common problem in patent drafting is that the patent attorney focuses on describing and protecting the product that the client has invented, rather than describing and protecting the idea that the client has invented.

After all, the product is just one specific configuration of an idea. An idea can have many different configurations, and by protecting the product rather than the idea, we limit the possible protection for the idea unnecessarily.

Above all, it is important to remember that the task of the lawyer and patent attorney is much more than just describing what the inventor thinks he has invented – which is usually a product. The lawyer and patent attorney must describe and claim everything that is inherent in the “invention” – to describe the idea that is at the heart of the client’s invention.

Dependent Claims as a Factor Contributing to Broad Protection

To address the problem presented in this article, dependent claims can be used as a place to store the various configurations of the patent (the product).

That is, in the independent claim we will protect the general idea, while in the dependent claims we will protect the products that are derivatives of the general idea.

The need for a dependent claim arises when the examiner in the examination process considers the independent claim to be too general, or that the independent claim falls within the scope of a prior publication. In such a case, we can, within the framework of the examination process, combine the independent claim with one of the dependent claims and return to the examiner and request a re-examination.

If we did not have dependent claims in the patent and we wanted to add a new configuration to the patent or a new material, this would be considered new knowledge that negates the patent’s right of priority and may even invalidate the patent due to prior self-publication.

That is, dependent claims serve as ammunition for us to deal with the examination process and allow us to amend the patent during the examination process without waiving the patent’s right of priority.

And it is they that allow us to take risks and draft the patent in a narrow form at the beginning, and only at the examination stage, if necessary, to add additional conditions to the independent claim (the heart of the patent).